On Thursday, Texas Wesleyan received a flood of new students from Fort Worth.

Sponsored by the School of Education, the annual Science and Reading Camp brought hundreds of city students from elementary school to high school to campus for a day of learning.

Most are immigrants and refugees who are not proficient English speakers, according to an email from Wesleyan student Amanda Merrill. Because Wesleyan has both bilingual education and ESL specialization programs, it is a perfect opportunity for students in these programs to practice working with students with limited English proficiency.

The groups of students were led by education major volunteers, who guided them around campus and assisted with their activities, said Elizabeth Ward, associate professor of education.

Each year’s activities are different. This year the students are doing a cart and ramp experiment in which they race carts down a ramp to measure speed and record who goes fastest and finishes first, Ward said.

Last year, students were read a book about a boy who had an amazing idea about how to build a car, according to Crystal Webb, an education major volunteer. After the story was over, students grouped together and discussed how they would make their own cars; they also designed them.

“It was really fun to see the smiles on the kid’s faces, and how the engaged with the other college students,” Webb said.

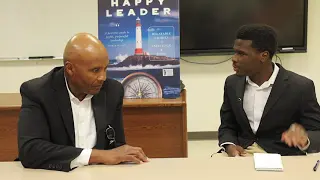

Education professor Robert J. Wilson said he started the camp about 18 years ago, when he realized that elementary students weren’t getting enough science and reading; nor did they realize there is school after high school. The first Wesleyan visitors were fifth graders. Wilson put the camp together, teaching students science and reading and giving them a tour of Wesleyan.

The camp continued in this way for about 10 years, Wilson said. Toward the end of that time, Wilson met people from a second Fort Worth Independent School District language center that primarily assisted children of immigrants and United Nations refugees.

Wilson said he was asked if he could teach the teachers at that center how to teach the same reading and science that the first group of students were learning. The next year, the teachers at the second center brought their students to camp; this represented between 250 and 500 students.

“I’m a good teacher, but I’m not that good,” Wilson said.

It was decided that the camp would be a perfect opportunity for education majors to get hands-on teaching experience, Wilson said. He left out the fact that none of the students they would be teaching spoke English; most of the children taken in by the second language center have spent their formative years in refugee camps.

“That is a real situation that our students will have when they go to set up their first classrooms,” Wilson said.

The camp is just as much for the education majors as it is for the second language students, Ward said; it lets the education majors develop soft management skills that are hard to develop without hands-on experience.

The camp’s biggest challenge is ensuring students understand what is going on and can learn from it, Ward said. This means the lesson must be brought down to the “comprehensible input,” meaning it is at a point where the children can understand,participate in and make meaning of what is going on in the experiment, such as this year’s car races.

“Our students learn more from the experience than their students,” Ward said.

Photo by Lacey Mosier.

![Pippin, played by Hunter Heart, leads a musical number in the second act of the musical. [Photo courtesy Kris Ikejiri]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Pippin-Review-1200x800.jpg)

![Harriet and Warren, played by Trinity Chenault and Trent Cole, embrace in a hug [Photo courtesy Lauren Hunt]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/lettersfromthelibrary_01-1200x800.jpg)

![Samantha Barragan celebrates following victory in a bout. [Photo courtesy Tu Pha]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/20250504_164435000_iOS-834x1200.jpg)

![Hunter Heart (center), the play's lead, rehearses a scene alongside other student actors. [Photo courtesy Jacob Sanchez]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/thumbnail_IMG_8412-1200x816.jpg)

![Student actors rehearse for Pippin, Theatre Wesleyan's upcoming musical. [Photo courtesy Jacob Rivera-Sanchez]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Pippin-Preview-1200x739.jpg)

![[Photo courtesy Brooklyn Rowe]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/CMYK_Shaiza_4227-1080x1200.jpg)

![Lady Rams softball wraps up weekend against Nelson Lions with a victory [6 – 1]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-04-100924-1200x647.png)