In August, senior theater major Julian Rodriguez wrote an open letter to Texas Wesleyan University on Facebook about why he could not return in the fall and finish his degree.

“Here I sit losing everything I have worked so hard for because you decided to implement a payment plan policy that has so negatively impacted many of your students,” wrote Rodriguez, who had been a resident assistant and a member of numerous student organizations including Ram Squad.

“Smaller. Smarter? Not anymore,” he wrote.

Rodriguez is one of the students that have left Wesleyan since deregistration began in August. One hundred and 10 students are no longer at the university, Vice President of Finance and Administration Donna Nance wrote in an email.

The deregistration policy at Wesleyan was first implemented this semester. The university’s website states that students registered for classes must “assume financial responsibility for tuition and fees as established by the University and approved by the University Board of Trustees. Students must meet financial obligations or will be dropped from classes.”

Students were deregistered from classes starting in August if they had not paid their bill in full or set up a payment plan.

Graphic by Hannah Lathen

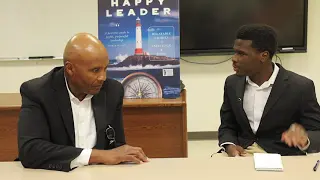

Vice President of Enrollment, Marketing and Communications John Veilleux said the policy was put in place because the school was finding itself in debt at the end of each semester from students not paying their bills.

“Whether that be fall, whether that be spring, students are coming in, they are signing up, taking out debt, in some cases, many thousands of dollars and then they are not able to pay that debt,” Veilleux said. “So that causes a couple of issues.”

The first issue is that it puts the student in debt to the university.

“That is unfair to the student because then that student can’t get their transcript. That student can’t move on to another university,” he said. “They are sort of locked in because they now have this debt that they have to pay off.”

The second issue, Veilleux said, is that Wesleyan can’t appropriately budget for the school year and then work within it without funds from student enrollment.

“By bringing in students into the university and not providing that revenue or making arrangements to pay for it, it doesn’t help the university meet its budget obligations and therefore bills, lights, paying faculty, making sure kids have supplies in the classroom or whatever the case may be, all the various costs that go with running a university,” he said.

Veilleux said last year Wesleyan budgeted to be $600,000 in bad debt but ended up being more than $1 million in bad debt because students did not pay their bills.

“We need to put in best practices that allow us to meet our financial obligations as a university as a business,” he said. “We don’t do the student a favor and we don’t do the university a favor by not being able to pay our bills.”

The deregistration is set to stay in place, he said.

“There are going to be opportunities that go along with the service of deregistration. I know there have been some hiccups along the way with payment plans,” he said. “I think we want to make sure we have more flexible payment plans out there.”

Dean of Freshman Students Joe Brown said the deregistration policy affects returning students the most.

“For them it is a real shock and when you factor in the same time the university put a cap on hours, the 16-hour cap, with some exceptions, returning students were hit with the 16-hour cap, plus, ‘OK. You are going to have to set a payment plan up,’” Brown said.

Brown said the university lost some students because they were unable to make the first payment of the payment plan. However, he sees both sides.

“I see why we can’t have $1.1 million in student debt for students who chose to come here who basically sat in classes, were taught, faculty were taught, labs were done, and they basically had what we call goods and services and then end up not totally paying the balance,” he said.

Student Government Association President Alyssa Hutchinson said she was one of the returning students who got deregistered. She said her issues with deregistration are with how the policy was implemented.

“That was a frustrating experience,” Hutchinson said.

She said that for three weeks before the first deregistration, she was passed around from office to office trying to figure out when her scholarships would be applied to her account before she would ultimately be pulled from classes.

“No one person could deal with what I was trying to deal with, they just kept sending me to another person,” she said. “I have heard that experience has happened to a lot of people in having to do that. It was very scary.”

Hutchinson said much of her frustration stems from when Financial Aid introduced the policy to SGA last semester. She said it was presented to the organization with three options.

“You could either pay in full, make a payment plan or you could talk to financial aid and give them whatever they need to not get deregistered,” Hutchinson said. “You have told them your situation.”

The three options were the only reason SGA supported deregistration, she said.

“Whenever I got deregistered, I had asked them what I could do to not get deregistered, the cashier’s office told me I could either make a payment plan or pay it in full,” she said. “We were literally told one thing and given another.”

![Pippin, played by Hunter Heart, leads a musical number in the second act of the musical. [Photo courtesy Kris Ikejiri]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Pippin-Review-1200x800.jpg)

![Harriet and Warren, played by Trinity Chenault and Trent Cole, embrace in a hug [Photo courtesy Lauren Hunt]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/lettersfromthelibrary_01-1200x800.jpg)

![Samantha Barragan celebrates following victory in a bout. [Photo courtesy Tu Pha]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/20250504_164435000_iOS-834x1200.jpg)

![Hunter Heart (center), the play's lead, rehearses a scene alongside other student actors. [Photo courtesy Jacob Sanchez]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/thumbnail_IMG_8412-1200x816.jpg)

![Student actors rehearse for Pippin, Theatre Wesleyan's upcoming musical. [Photo courtesy Jacob Rivera-Sanchez]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Pippin-Preview-1200x739.jpg)

![[Photo courtesy Brooklyn Rowe]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/CMYK_Shaiza_4227-1080x1200.jpg)

![Lady Rams softball wraps up weekend against Nelson Lions with a victory [6 – 1]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-04-100924-1200x647.png)