The Texas Wesleyan Athletic Training Staff passed out a “Concussion Fact Sheet for Faculty” at a campus wide faculty meeting before class started.

“The original idea actually came from one of our students Tammy Titlow who was doing a project for an English class,” Dr. Pamela Rast said, the Athletic Training Program Director.

Titlow came up with the idea for the proposal for a video project where the students were not allowed to speak and had to explain the proposal through cue cards, Rast said, a professor and the chair for the department of kinesiology.

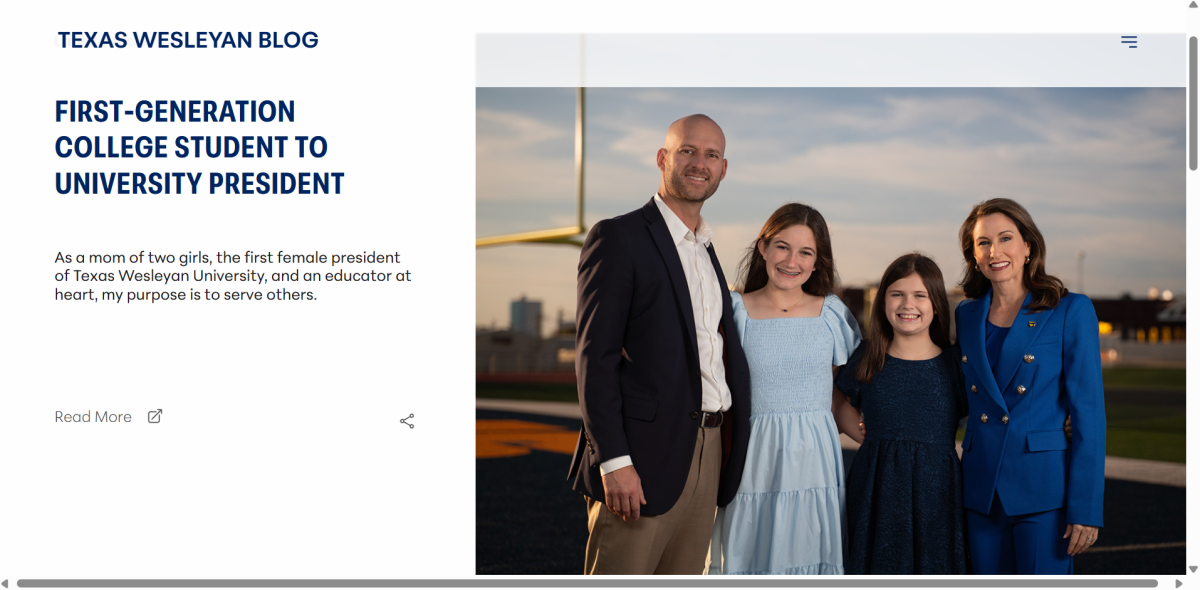

“It was something that at Texas Wesleyan we could really do because we are smaller,” Rast said. “We as faculty get to know our students so we know when there is something off with one of our students.”

Wesleyan’s smaller size is an advantage because at a bigger school the professors don’t know their students as well which makes spotting subtle concussion symptoms almost impossible, Rast said.

The main reason for the cards is that so many athletes don’t report concussions so they can continue to play and many others don’t realize they have a concussion.

“[The athlete] may not develop symptoms of concussion right away,” Rast said. “It might be something that happens kind of over time. So, if a faculty member recognizes some of these signs or symptoms… now we have a mechanism by which that faculty member can get in touch with the athletic training staff to call that athlete in, and ‘let’s just take a look.’ It’s all about that athlete’s safety.”

The addition of football brought 125 young men to campus that are at risk for a concussion, and this addition prompted the creation of the concussion fact sheet, Rast said.

“Even though we are NAIA,” Rast said, “we have adopted some of the NCAA best practices for concussion management, and also in those practices is not just return to play but also return to learn. We have two members of our faculty that are familiar with concussion that are return to learn case managers.”

When an athlete has a concussion and they are out of class for a while or returning to a normal class schedule one of the return-to-learn case managers will communicate with the athlete and the faculty so everyone is clear on the athlete’s status, Rast said.

“There is a number essentially where if you’re a professor… it’s going to be a direct phone call to the athletic training facility,” Rast said. “We’ve given a list of the athletic trainers that are working with each sport so that that faculty member can call the athletic training facility and talk directly to that athletic trainer that is working with that team.”

If the team specific trainer can’t be reached then the faculty can call Dr. Rob Thiebaud and Dr. Pamela Rast, return to learn case managers, and they will notify the correct trainer, Rast said.

“Once the athletic training staff is notified that there is suspicion,” Rast said, “then those health care provides will get in touch with the athlete… do some basic testing that would identify whether this individual may have a concussion.”

Testing for a concussion doesn’t require fancy equipment or a trip to the hospital the athletic trainers administer some special diagnostic tests Impact and SCAT 5 to determine if the athlete needs more care, Rast said.

“Those individuals have gone through a baseline test called an impact test,” Rast said, “what would happen is after an individual has been diagnosed with a concussion, then that baseline test is compared to an additional test several days into their recovery and then again another several days into their recovery.”

The athletic training program aims to get athletes physically well not just so they can compete but so that they get back in the classroom as quickly and safely as possible, Rast said.

“Our main concern as faculty, obviously, is that our students receive a good education,” Rast said, “and that we put them in a situation where they can be successful academically. We want to make sure that we’re not stressing their brain too much or stressing their brain too little.

There is always new research about the brain and concussions being published, and there has been more information come out about how concussions can affect an athlete in the classroom, athletic director Steve Trachier said.

“They could have headaches or light sensitivity to the eyes or difficulty concentrating or remembering things,” Trachier said. “It’s important that professors understand that this is a real thing, and that they be able to work with the students and accommodate them when they might be experiencing some of these effects.”

The athletic training department had this idea and the athletic department is in full support because protecting the athletes is the most important thing, Trachier said.

“I think its driven by the athletic training department I think that Dr. Rast’s department will be the most knowledgeable in brain injury brain trauma and the effects of that,” Trachier said.

Football, men’s soccer and women’s soccer are the most at risk for concussion, Trachier said.

“When you participate in sport,” Trachier said, “there’s always a chance that you fall hit your head whatever so it’s always been there.”

The coaches, and athletic trainers are continually learning how to best diagnose a concussion, make sure that players don’t reenter a game, and what to do to best treat a concussion, Trachier said.

“Once again, we’re trying to take every precautionary measure we can to make the game safer,” Trachier said.

“I looked at it from the perspective of it was a proposal for an English project,” Tammy Titlow a senior liberal studies major, “but we’re so focused on our smaller smarter here and what can we do to take care of our athletes.”

Some of the research Titlow used for her project stated that parents would’ve gotten their children care if they had known the symptoms of concussion, Titlow said.

“[The athletes] come to school here, there isn’t a parent here, their buddy on the football team isn’t going to tell them to go report. So, I looked at it as ‘who’s next?’”

Since Wesleyan is smaller faculty can communicate with most of their students daily and pick up on any behavioral changes, Titlow said.

“So, we’re the caring person,” Titlow said, “we’re the one that’s going to reach out to the student and say, ‘something’s not right. Let’s go get you looked at,’ and so that’s how I approached the whole project.”

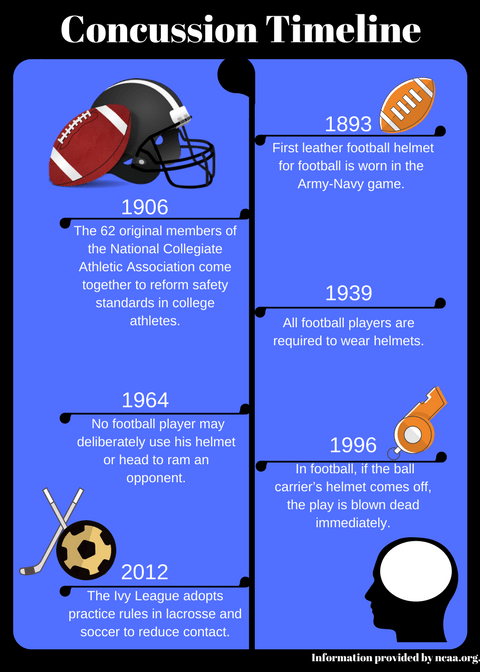

Infographic by Shaydi Paramore

Infographic by Shaydi Paramore

![Pippin, played by Hunter Heart, leads a musical number in the second act of the musical. [Photo courtesy Kris Ikejiri]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Pippin-Review-1200x800.jpg)

![Harriet and Warren, played by Trinity Chenault and Trent Cole, embrace in a hug [Photo courtesy Lauren Hunt]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/lettersfromthelibrary_01-1200x800.jpg)

![Samantha Barragan celebrates following victory in a bout. [Photo courtesy Tu Pha]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/20250504_164435000_iOS-834x1200.jpg)

![Hunter Heart (center), the play's lead, rehearses a scene alongside other student actors. [Photo courtesy Jacob Sanchez]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/thumbnail_IMG_8412-1200x816.jpg)

![Student actors rehearse for Pippin, Theatre Wesleyan's upcoming musical. [Photo courtesy Jacob Rivera-Sanchez]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Pippin-Preview-1200x739.jpg)

![[Photo courtesy Brooklyn Rowe]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/CMYK_Shaiza_4227-1080x1200.jpg)

![Lady Rams softball wraps up weekend against Nelson Lions with a victory [6 – 1]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-04-100924-1200x647.png)

![The Texas Wesleyan University women's golf team walks the course. [Photo courtesy of Corrina Griffin]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/rounds-902x1200.jpg)