World renowned historian and author, Dr. Monica H. Green, presented a lecture on The Black Plague to a packed auditorium on Tues. Feb. 18, 2025.

Professor Alistair Maeer, who organized the visit, introduced the speaker.

“We are exceedingly privileged and honored to have someone of this caliber speaking at Wesleyan,” Maeer said.

Dr. Green’s accolades precede her. She studied at Barnard College and Princeton University, where she earned a master’s and a doctorate degree. She is the recipient of the John Nicolas Brown prize and the Margaret W. Rossiter History of Women in Science prize. She was elected a fellow to the Medieval Academy of America, and she has written several prize-winning books.

“I think society in general thinks that history is one way and science is another, and they don’t ever overlap the two, but there is an extraordinary amount of mutual understanding and benefits we can get from Green’s lecture,” Maeer said.

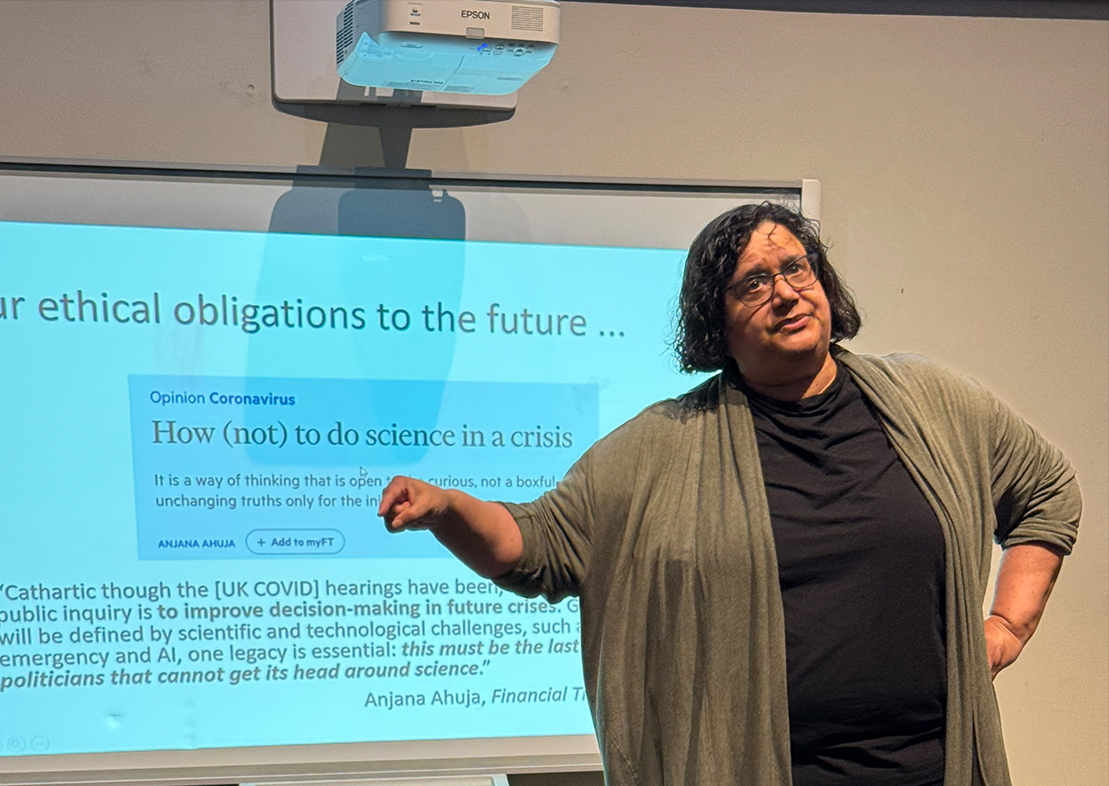

Green’s lecture covered a variety of topics related to The Black Plague but focused on her research discovering its origins. Given the world’s recent brush with the COVID pandemic, her research brought recent history and science to the forefront.

“We only get pandemics or even epidemics, when it has disrupted that normal course of affairs,” Green said.

The plague lasted 500 years. Dr. Green shed light on how these events happen.

“The biological definition of the plague would be that a fairly sudden dissemination of a marmot derived strain of yersinia pestis, a single cell bacterium that causes plague,” Green said.

Basically, animals were disrupted by an environmental change, and plague was the evolutionary consequence.

“It’s a question about the movement of people, movement of animals, ecologies, various other things that we need to ask,” she said.

Sue Eliason, English major, enjoyed learning about the way ecology affected the Earth in medieval times.

“I loved learning about the animals that were responsible only because humans interrupted their cycle,” Eliason said.

Green continued her presentation explaining how rapidly plague moved through the lymph system of the body before a very quick death.

Green cited an ancient account of lives in Baghdad during the plague.

“In the end, it became so bad that they could not even carry the dead to the Tigris on account of the number who were dying, ,” she said.

Green continued her talk, as she dove further into her career as a medieval historian.

“One of the things that I would love universally to be true, is that that everybody is skilled in historical thinking, not factoids, that memorize this or memorize that,” Green said. “How do you formulate some answer for where you would look for evidence to answer this?”

Green encounters people, on occasion, who may doubt her scientific and historically backed research.

“My work as a teacher is that it is not my job to pound into people’s brains a truth, a single truth. There are things that I think are true, and there are many things that I think we can demonstrate,” she said.

With an impressive number of accolades, it can be hard not to be star struck by Green. The audience can feel her passion for her subject throughout her presentation. She ended her time at TxWes with a few words of helpful advice for young scholars.

“I think of all the people that I look at and that I’ve encountered as academics, the ones I admire most or envy most are the ones that are truthful, the ones that are kind,” Green said.

Ultimately, she advised scholars to search for and understand what their own personal moral codes are.

“Your moral core will be what guides you in making those kinds of daily decisions,” she concluded.

Green is currently working on a forthcoming book titled “The Black Death: A Global History.”

![Pippin, played by Hunter Heart, leads a musical number in the second act of the musical. [Photo courtesy Kris Ikejiri]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Pippin-Review-1200x800.jpg)

![Harriet and Warren, played by Trinity Chenault and Trent Cole, embrace in a hug [Photo courtesy Lauren Hunt]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/lettersfromthelibrary_01-1200x800.jpg)

![Samantha Barragan celebrates following victory in a bout. [Photo courtesy Tu Pha]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/20250504_164435000_iOS-834x1200.jpg)

![Hunter Heart (center), the play's lead, rehearses a scene alongside other student actors. [Photo courtesy Jacob Sanchez]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/thumbnail_IMG_8412-1200x816.jpg)

![Student actors rehearse for Pippin, Theatre Wesleyan's upcoming musical. [Photo courtesy Jacob Rivera-Sanchez]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Pippin-Preview-1200x739.jpg)

![[Photo courtesy Brooklyn Rowe]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/CMYK_Shaiza_4227-1080x1200.jpg)

![Lady Rams softball wraps up weekend against Nelson Lions with a victory [6 – 1]](https://therambler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-04-100924-1200x647.png)